Blog

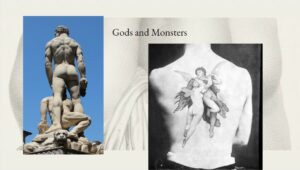

Museum Bums explore the inspirations for John Addington Symonds – OutStories and the IGRCT

Posted on 10th November, 2023

We were so excited to be invited to give the annual John Addington Symonds lecture for OutStories Bristol and the Institute of Greece, Rome, and the Classical Tradition (IGRCT) back in October, and we’ve just got round to typing it up so you can read it too! So here it is, here you go, we got a lovely introduction from Dr Ian Calvert, Deputy Director of the IGRCT, and we’ve added in some of the images from the presentation which was playing behind us while we were giving the talk:

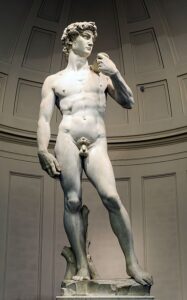

Hello, we are Jack Shoulder and Mark Small, and we are Museum Bums. We’ve been celebrating and sharing the bums of fine art in museums, galleries, libraries, archives and anywhere else that can be described as a cultural space since 2016. In September 2023 we published our book “Museum Bums: A Cheeky Look at Butts in Art”. Our book looks at everything from sculpture, paintings, abstract art and objects that were never meant to be in a museum but ended up there anyway, and depict bums. Our book is unashamedly queer, feminist, socially conscious, and we’re hoping it gives people an accessible way into fine art and art history in a way that hasn’t been done before.

We were very excited to be invited by Chris to speak for the annual John Addington Symonds lecture for OutStories and the Institute of Greece, Rome, and the Classical Tradition… until we realised that that meant we had to write something clever. So we had a little panic and we did as much research as we could without immediate access to university libraries, and we ended up discovering that there are some strong themes in Symond’s life and works which fit very nicely into the themes of the 6 chapters of our book.

But before we get going properly, let’s pause and think: was John a ‘butt’ guy? A fan of the callipygian keister? In his writings about the men he found beautiful, he speaks eloquently about “splendid eyes and throat, athletic and magnificent curve of broad square shoulders, and imperial poise of sinewy trunk upon well-knitted hips and thighs” and waxes lyrical about the “poise of trunk upon massive hips; thick and sinewy thighs.” John did write about a “plump fair-haired boy, called Ainslie, whom we dubbed Bum Bathsheba because of his opulent posterior parts.” The bum part of that nick-name is self evident. Bathsheba is a character from the bible, whom King David (more about him later) saw bathing and so desired.

Here’s Jean Leon Gerome’s “Bethsabée”, 1889, where you can see King David top left on the balcony having a good look:

Whilst on the Grand Tour, JAS described a handsome Italian man’s “rosy nipples . . . marble man-spheres . . . lustrous gland”.

Marble Man-spheres is *quite* the image!

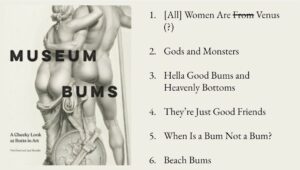

Our first chapter is called “[All] Women are From Venus”, and this looks at the depiction of women and female form in art from pre-historic fertility idols through to the 19th century resurgence in the architecture, art and philosophies of the neoclassical.

As a 19th century writer, poet and philosopher with a strong focus in his works on classical subjects, John Addington Symonds obviously fits very nicely here. John Addington Symonds was a rich, white, upper class Bristolian man in the nineteenth century, so obviously he went on The Grand Tour. The Grand Tour was a spirit journey for those that could afford it around Europe and the Mediterranean to take in what remains of the ancient classical cultures had been uncovered by that time, those bits which were too heavy or notorious not to have been stolen already, and it fuelled the fashion for the neo-classical from the 18th and 19th centuries onwards in Northern Europe, in terms of architecture, art, philosophy and aestheticism, in tandem with the already well-established culture of Christian art.

As a 19th century writer, poet and philosopher with a strong focus in his works on classical subjects, John Addington Symonds obviously fits very nicely here. John Addington Symonds was a rich, white, upper class Bristolian man in the nineteenth century, so obviously he went on The Grand Tour. The Grand Tour was a spirit journey for those that could afford it around Europe and the Mediterranean to take in what remains of the ancient classical cultures had been uncovered by that time, those bits which were too heavy or notorious not to have been stolen already, and it fuelled the fashion for the neo-classical from the 18th and 19th centuries onwards in Northern Europe, in terms of architecture, art, philosophy and aestheticism, in tandem with the already well-established culture of Christian art.

We make the point in this chapter that the output of the neoclassical tradition is almost exclusively by male hands, despite extensively depicting the female form through statues and paintings of the Roman goddess, Venus. Venus was the goddess of fertility, but in the 19th century the virtues of her fertility were seen through predominantly male eyes and created by male hands (notable exceptions to this rule include 19th century female artists such as Ellen Sharples, who founded our own Royal West of England Academy.)

Venus and Adonis by Titian, 1550s, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

To bring it back to a place of JAS: Venus is a figure that he speaks of identifying with. Upon reading Shakespeare’s ‘Venus and Adonis’ he had this reflection:

“In some confused way I identified myself with Adonis; but at the same time I yearned after him as an adorable object of passionate love. Venus only served to intensify the situation. I did not pity her. I did not want her. I did not think that, had I been in the position of Adonis, I should have used his opportunities to better purpose. No: she only expressed my own relation to the desirable male. She brought into relief the overwhelming attraction of masculine adolescence and its proud inaccessibility. Her hot wooing taught me what it was to woo with sexual ardour. I dreamed of falling back like her upon the grass, and folding the quick-panting lad in my embrace.”

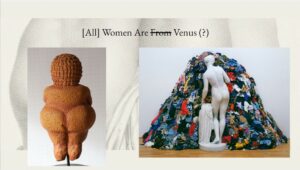

Sticking with the classical and the neoclassical, our second chapter is called “Gods and Monsters” and this looks at the veritable bevvy of heroes and villains in myths and legends who are depicted in our museums, galleries, archives, and libraries. We look at why is it heroic to be naked? How confusing is it that Theseus and the Minotaur appear to be loving, not fighting? And just how badly wrong did 19th century artists get it when whitewashing every myth they could get their hands on.

Sticking with the classical and the neoclassical, our second chapter is called “Gods and Monsters” and this looks at the veritable bevvy of heroes and villains in myths and legends who are depicted in our museums, galleries, archives, and libraries. We look at why is it heroic to be naked? How confusing is it that Theseus and the Minotaur appear to be loving, not fighting? And just how badly wrong did 19th century artists get it when whitewashing every myth they could get their hands on.

John Addington Symonds is just the right era to supplement his Grand Tour with trips to the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and his local Bristol Museum and the Art Gallery next door (our talk was at the University of Bristol), all of which exhibited either the original statues, friezes and objects, or made copies using plaster casts for those which weren’t readily available.

Symond’s written back-catalogue includes so many references to classical characters. Just a snapshot highlights “The Love-Tale of Cleomachus,” “Theron,” “The Clemency of Phalaris,” “The Elysium of Greek Lovers,” “Cratinus and Aristodemus,” “The Tale of Leutychidas and Lynkeus,” “Dipsychus Deterior,” “Diocles,” “Damocles the Beautiful,” “Genius Amoris Amari Visio,” “Callicrates,” “Gabriel” and “The Lotos Garden of Antinous.” It’s worth noting that these are just the works which have survived to be studied by scholars such as Rictor Norton. We know that a young John Addington Symonds felt guilty enough about his written poetry, that he locked his collected works in a black tin box, and threw that box in the River Avon.

It’s clear that the neoclassical period invited classical figures into those new-fangled inventions: the public museum, and with 19th century influencers like Symonds spreading the word in such eloquent ways, we’re very happy that we get to see so much of it still today.

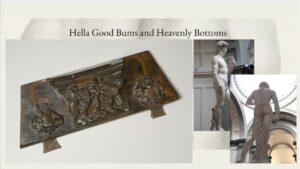

Chapter 3 is called “Hella Good Bums and Heavenly Bottoms” and looks at bums in religious art. Because of the scope of what we had available (largely researching the book during lockdowns), we focus on Western religious art, which is obviously mostly Christianity. If we get the chance to write a follow-up book, one of our aims is to explore further afield and see what bums we can find in religious art further afield. Having said that, there are more bums in churches than you might expect!

Chapter 3 is called “Hella Good Bums and Heavenly Bottoms” and looks at bums in religious art. Because of the scope of what we had available (largely researching the book during lockdowns), we focus on Western religious art, which is obviously mostly Christianity. If we get the chance to write a follow-up book, one of our aims is to explore further afield and see what bums we can find in religious art further afield. Having said that, there are more bums in churches than you might expect!

Bristol Museum and Art Gallery hold a collection of mediaeval misericords from Bristol Cathedral, rescued from destruction when the Victorians fancied a modern refit in their already centuries old cathedral (for more on this you can read Andrew Foyle’s excellent Bristol Pevsner guide!) Misericords are the hinged seats in church quires for choirs and clergy to perch on during long sermons. They have an amazing precedent for non-religious depictions carved into them, including mermaids, the green man, completely secular scenes, and bizarre tableaus like monkeys riding goats. Fortunately for us, the mediaeval carpenters of Bristol also felt like putting a few bums in. It makes us very happy to think that John Addington Symonds may have sat on these callipygian seats while waiting for a rendezvous with his young lover, William Fear Dyer in 1858 (more on him later).

John Addington Symond’s poem, “The Meeting of David and Jonathan” lays out the relationship of David and Jonathan from the bible. You’ll have heard of this David as “Michelangelo’s David”, who’s just about to defeat the Goliath, but you’ll also know him from the Christmas hymn, “Once in Royal David’s City”. That David the sheepherder ended up being King David of Judah, or Israel, and his story is most well-disseminated through the Hebrew Bible book of Samuel. This is a queer love story and Symonds doesn’t shy away from that:

“In his arms of strength / Took David, and for some love found at length / Solace in speech, and pressure and breath / Wherewith the mouth of yearning winnoweth /Hearts overcharged for utterance. In that kiss / Soul into soul was knit and bliss to bliss.”

Steamy stuff!

David’s queerness was more well-known and accepted than it is today. David had several lovers in his narrative – we’ve encountered two today (Bathsheba and Jonathan), and those in the know in 19th century society used references to David, particularly David and Jonathan, as a way of signalling their own attraction to men. Which brings us nicely onto…

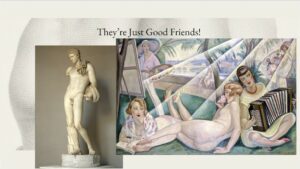

Our fourth chapter is called “They’re Just Good Friends!”, and this is our chapter exploring queer representation in art, how to spot it, and why it’s not as visible as it could be (spoiler: the answer is straight curators).

Our fourth chapter is called “They’re Just Good Friends!”, and this is our chapter exploring queer representation in art, how to spot it, and why it’s not as visible as it could be (spoiler: the answer is straight curators).

We look at Achilles and his overwhelming grief after the death of his “companion” Patroclus; 19th century Dutch artist, Gerda Wegener and her trans love, Lili Elbe, and the overt queer gaze in their paintings; the pert and perky bisexual god that is Apollo (- if you ever want to see three depictions of Apollo that look so bitchy and judgemental that they look like they could be in Mean Girls, head to The Museum of Classical Archaeology in Cambridge); Paul Cadmus’ almost-photorealistic 20th century paintings of beautiful men sharing a bathroom or enjoying themselves at the beach; and John Singer Sargent’s paintings of First World War soldiers having a nude snooze on a river bank after what must have been some athletic skinny dipping!

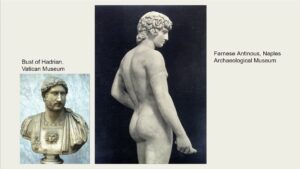

The straightwashing and oppression of queer art is an obvious strong theme with the works of John Addington Symonds. If the majority of 19th, 20th and 21st century society wasn’t skewed towards heterosexuality as normal, good and right, Symonds’ work could be much more famous, much more celebrated, and much more complete! Fortunately for us, the good people of OutStories and the IGRCT do have this annual event to share and celebrate the impact that Symonds has had. One of the most famous queer couples depicted in cultural spaces is Antinous and Hadrian, and John Addington Symonds doesn’t let us down! Here he’s describing Antinous acting as Hadrian’s cup-bearer at a feast:

He rose, and from his shoulder’s ivory

He rose, and from his shoulder’s ivory

The veil fell fluttering to his rounded thigh:

Naked he stood; then on his forehead set

A crimson wreath of lotos, cool and wet,

Fresh from the tank, with ivy mixed; and bound

Roses about his breast; and from the ground

A tendril-tangled thyrsus raised, and flung

The quivering leaves aloft that clasped and clung.

Next half the lustre of his limbs he hid,

Like some night-reveller or Bassarid

Fresh-flown from Indian thickets, with the fur

Of panthers streaked and spotted, sleek with myrrh

And musky-fragrant. In his hand a bowl,

Carved of one beryl, soft as if a soul

Throbbed in its flush, he took, and called his crew.

They to their Bacchus with loud laughter flew,

Tossing flame faces, twinkling tiny feet

In measured madness to the timbrel’s beat—

Wild hair behind them flying, loosened zone,

And flowers about their flanks for girdles strewn.

Girls were they, girls with vine-leaves garlanded,

Or jasmines white as their own maidenhead!

Boys too; ye gods, the beauty of those boys,

Lithe as young leopards! the soul-thrilling noise

Of their shrill voices!—Bells are at their feet,

And silver armlets, tinkling as they meet,

Make the air mad.

This is an excerpt from “The Lotos-Garland of Antinous”. For those who don’t know, Antinous was the young lover and companion of the Roman Emperor Hadrian – yes, him who did the wall. Antinous entered the pantheon of Roman gods after his potentially suspicious death, when Hadrian used his divine right to deify the beautiful youth. There’s obviously no straight way to interpret the way these two love each other in Symond’s poem, but we’re sure people have tried!

Incidentally, it’s difficult not to draw comparisons between Hadrian and Antinous, and John Addington Symonds and his love affair with Bristolian church organist, William Fear Dyer in 1858. Dyer was a younger man from a different class, their relationship was known about and understood as real, but generally discouraged, and ultimately was ended by parties other than the couple. Symonds and Hadrian even have similar beards!

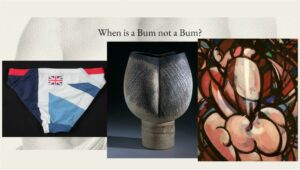

Chapter 5, don’t worry, we’re nearly there! Is called “When is a Bum not a Bum?”, and this is where we get a bit more abstract and philosophical. In the book this is where we explore how seeing Tom Daley’s olympic medal-winning speedos in the Museum of London makes it nigh-on impossible not to think about his olympic medal-winning bum. We look at abstract art, where that might be an elbow, or a knee, but there’s also the possibility that bums are present, and we look at negative space bums – chairs where the shape of the bum has been carved in, but what’s there is the space around the bum instead of the bum itself.

Chapter 5, don’t worry, we’re nearly there! Is called “When is a Bum not a Bum?”, and this is where we get a bit more abstract and philosophical. In the book this is where we explore how seeing Tom Daley’s olympic medal-winning speedos in the Museum of London makes it nigh-on impossible not to think about his olympic medal-winning bum. We look at abstract art, where that might be an elbow, or a knee, but there’s also the possibility that bums are present, and we look at negative space bums – chairs where the shape of the bum has been carved in, but what’s there is the space around the bum instead of the bum itself.

We had to get a bit creative to link this to John Addington Symonds, but we think we’ve managed it. So in the same way that in the art in the chapter there are allegorical bums, or negative space bums, we noticed that John Addington Symond’s poetry stops shy of describing butts. For Antinous we get “his rounded-thigh” and his “orbed breast”, lots of description of his beautiful naked form. Describing his sights on the Grand Tour, Symond’s writes about the “rosy nipples . . . marble man-spheres . . .and lustrous glands” of the sights he sees. We know Symonds was a massive fan of Walt Whitman, and owned an extensive library of his works. Whitman also famously used codified or allegorical ways to demonstrate same-sex love and passion in his works, so we know he was familiar with that style.

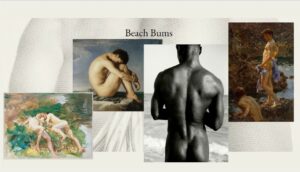

Finally, our concluding chapter is entitled “Beach Bums” and it highlights the propensity for paintings of twinks and twunks at the beach, who’ve all accidentally forgotten their swimming trunks. If you described a painting of a beautiful nude youth frolicking at the beach, created in the 19th century, there’s a strong bet that you would end up with a Henry Scott Tuke painting. Tuke was prolific in his works portraying healthy strong men in clean sea air and representing idyllic natural beauty in their nude forms. This art was a hit for those who in contrast lived in dirty dank cities where the air was foul with smoke and soot and if you were naked you were probably doing something sinful.

Finally, our concluding chapter is entitled “Beach Bums” and it highlights the propensity for paintings of twinks and twunks at the beach, who’ve all accidentally forgotten their swimming trunks. If you described a painting of a beautiful nude youth frolicking at the beach, created in the 19th century, there’s a strong bet that you would end up with a Henry Scott Tuke painting. Tuke was prolific in his works portraying healthy strong men in clean sea air and representing idyllic natural beauty in their nude forms. This art was a hit for those who in contrast lived in dirty dank cities where the air was foul with smoke and soot and if you were naked you were probably doing something sinful.

John Addington Symonds corresponded a lot with Tuke, from Rictor Norton’s research we know that “He wrote to Henry Scott Tuke praising his Perseus for its delicate yet vigorous handling of the nude, and asked him for photographs of his pictures of the nude fisherboys of Falmouth.” Symonds had a collection of twenty-one photographs of original drawings by the homosexual painter Simeon Solomon sent to him from London in 1868, “chiefly classical subjects”. Symonds had “heard that William Hamo Thornycroft’s Mower was a Hermes in the dress of a working man,” and he eventually acquired photographs of several statues by Thornycroft including the Teucer (which is on display at Leighton House) and Warrior Bearing a Wounded Youth, which according to a letter to Edmund Gosse in 1884 were “the delight of my eyes & soul”. From this we think it’s fair to say he was a fan of the style.

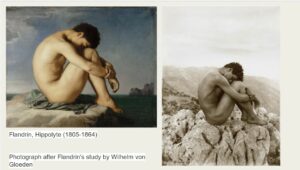

In a joyous coincidence, us and JAS are both drawn to Hippolyte Flandrin. JAS was thinking about painting vs photography and set up a compare and contrast thought exercise between the painting, and lacking a photograph, invited readers to consider “a living model in the same attitude.”

In a joyous coincidence, us and JAS are both drawn to Hippolyte Flandrin. JAS was thinking about painting vs photography and set up a compare and contrast thought exercise between the painting, and lacking a photograph, invited readers to consider “a living model in the same attitude.”

Luckily for us, we have plenty of photographs as this image has influenced many photographers over the years.

Symonds wrote “here is equally no doubt that Flandrin’s study is a painted poem, while the photograph of the nude model is only what one may see any morning if one gets a well-made youth to strip and pose.

What then gives Flandrin’s picture its value as an artistic product, as a painted poem? It tells no story, has no obvious intention; the painter clearly meant it to be as perfect a transcript from the nude, as near to the vraie vérité of nature, as he could make it. The answer is that, although he may not have sought to idealise, although he did not seek to express a definite thought, his picture is penetrated with spiritual quality. In passing through the artist’s mind, this form of a mere model has been transfigured. while it has lost something of the vivacity and salient truth of nature, it has acquired permanence, dignity, repose, elevation.

…

We cannot carve a naked man as wonderful as the youth stripped there upon the river’s bank before his plunge into the water.”

This is from Essays Speculative and Suggestive, 1890. The short excerpt is from a long essay that originally appeared in The Fortnightly Review, December 1887. Symonds’s deliberately provocative celebration of the superiority of nature over art is based on his close study of photographs of the male nude, of which he wrote to Edmund Gosse on 12 July 1890: “I have quite a vast collection now — enough to paper a little room I think. They become monotonous, but one goes seeking the supreme form & the perfect picture.”

In conclusion, we were very pleased to be able to find so much to say about John Addington Symonds in reference to our book “Museum Bums: A Cheeky Look at Butts in Art”, especially considering he’s not mentioned at all in the text. We have had to take liberties and stretch definitions on occasion, but we hope you’ve enjoyed exploring Symond’s work from a different angle with us today. And if, like Symonds, you’d like a collection of images “seeking the supreme form and perfect picture”, we have just the book for you!